Did changing MBS criteria reduce overuse of vitamin D testing?

Quick facts:

- In 2014 the government introduced new criteria aimed at reducing overuse of vitamin D testing.

- Although testing initially declined, the reduction was not sustained.

- Women who had more doctor visits and who had been tested previously were more likely to have vitamin D testing.

For women:

- If you are seeing your health practitioner and testing for vitamin D deficiency comes up in your conversation, Choosing Wisely Australia has 5 questions to ask your doctor or other healthcare provider before you get any test, treatment or procedure.

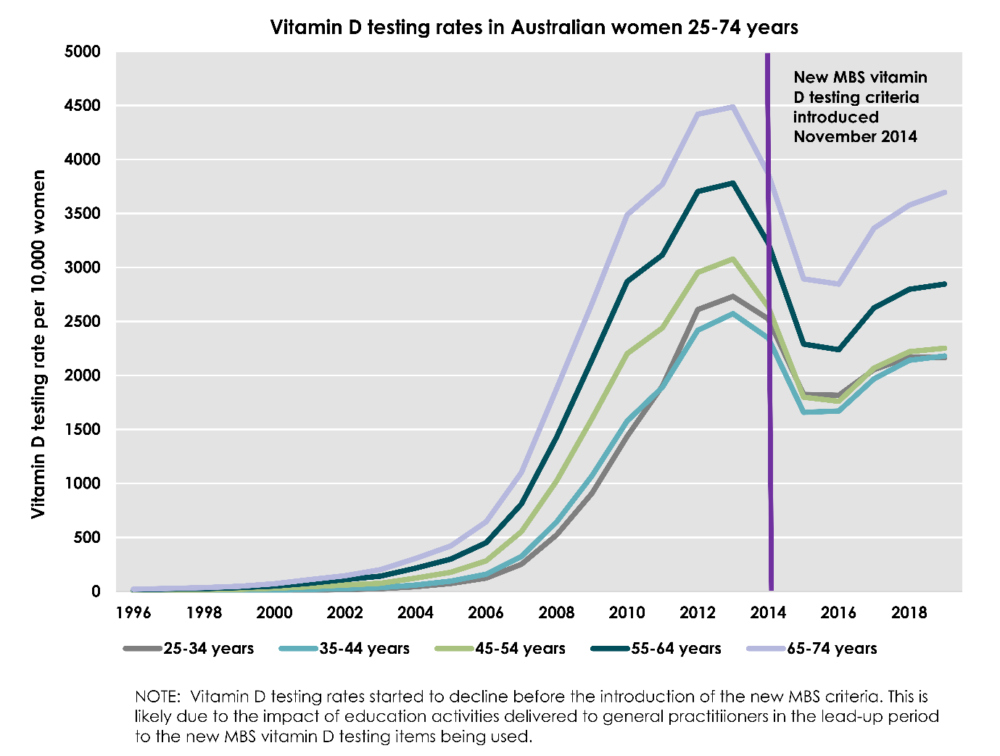

In the early 2000s, vitamin D testing in Australia increased by a dramatic 3587%. Concerns about the costs of potentially unnecessary testing led to a Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) review report, and the Australian government introduced new criteria in 2014 to limit testing to those at high risk of vitamin D deficiency.

Our study investigated:

- whether the new criteria changed testing rates in Australian women in the short or long-term; and

- what were the characteristics of women still undergoing tests.

Using Medicare data we looked at national vitamin D testing trends in Australian women aged 15 years and over before and after the introduction of new testing criteria. We also used data from 7,771 women (born 1946-1951) in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health to examine who was more likely to have a vitamin D test under the new criteria.

Vitamin D testing rates are trending up

Although vitamin D testing initially declined after the new criteria was introduced in 2014, this reduction was not sustained. Between 2016 and 2019 vitamin D testing rates in Australian women increased in all age groups.

Which women are getting Vitamin D tests?

Women who have signs or symptoms of vitamin D deficiency (e.g. women with signs or symptoms of osteoporosis or osteomalacia) require testing. Women who live at latitudes of less sun exposure and are more likely to have vitamin D deficiency also require testing. We wanted to know which other socioeconomic, demographic, health and health service utilisation factors were associated with vitamin D testing under the new criteria. We linked MBS data on the frequency of vitamin D testing to ALSWH survey data from the 1941-56 cohort.

As expected, we found that women who had a bone density test and those living at latitudes of less sun exposure were more likely to have a vitamin D test. Other predictors of having a vitamin D test under the new criteria were:

- having had a vitamin D test before the introduction of the new criteria

- visiting a GP more than twice a year (the strongest associations were in women who visited more than 8 times year)

Women who were less likely to have vitamin D testing were current smokers, lived outside a major city or had less than a high school education.

What next for vitamin D testing?

The introduction of the new criteria has not led to sustained declines in testing. The majority of women (56%) in the ALSWH 1946-51 cohort had at least one vitamin D test after the introduction of the new criteria. However, in the Australian population the prevalence of moderate and severe vitamin D deficiency is only 6% and 1% respectively.

The Royal College of Pathologists of Australia (RCPA) supports testing individuals at risk, and recommends testing to check the efficacy of supplementation. Because results can be affected by the season, they suggest testing is most appropriate at the end of winter. Both the RCPA and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) recommend against routine screening if there are no symptoms present.

High testing rates and repeated testing indicate women are either being routinely tested as part of a suite of regular blood tests, or a small proportion may be being monitored after starting vitamin D supplements. Testing of women living at latitudes of less sun exposure and in women who have had bone density testing suggests that some targeted testing is occurring in women with a higher risk of vitamin D deficiency.

However, it is clear from this study that some level of over-testing for vitamin D deficiency in Australian women is still occurring and other interventions will be necessary to reduce over-testing.

Contact:

Dr Louise Wilson

l.wilson8@uq.edu.au

Post-Doctoral Research Fellow

NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence on Women and Non-communicable Diseases (CRE-WaND), School of Public Health, The University of Queensland.

NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence on Women and Non-communicable Diseases: Prevention and Detection

Level 3, Public Health Building

The University of Queensland,

266 Herston Road

Herston, QLD, 4006

General enquiries

wandcre@uq.edu.au